This case is of interest because of the alleged abduction of Mr. Thomas from Barbados. Brent Thomas is a licensed gun and ammunition dealer and brought this claim through the High Court of Trinidad & Tobago (TT) against the Attorney-General and the Director of Public Prosecutions arising out of police investigations into his business, the issue of six search warrants and an abduction. The claim was heard before Mr. Justice Devindra Rampersad.

According to the judgment the evidence of Mr. Thomas was that at around 3 am on 5 October 2022, while asleep in his hotel in Barbados, he was jolted awake by shouts of “Police” and banging on his hotel door. Upon opening the door, he observed a large group of men dressed in black and armed with guns. The men then entered into the room, asked for a copy of his identification card and placed him in handcuffs. He was then put into a waiting police vehicle which conveyed him to a police station.

Mr. Thomas further stated that he was placed in a small cage at the back of a police van and left there until midday. He was not given any food, water or an opportunity to place a telephone call. Further, no explanation was provided as to why he was being detained. Around midday, the Barbadian officers transported him to another police station where he was kept in a cell until 5 p.m.

He was then taken to Grantley Adams International airport where he was taken into a small plane and taken back to TT. Rampersad J. stated that all of this evidence was unchallenged by opposing evidence.

It was on this basis that Mr. Thomas was seeking a declaration that the arrest, detention and forcible abduction within, and the removal from Barbados to TT, at the behest of the State of TT acting through its servants and or agents, were grossly abusive, unconstitutional, unlawful, unnecessary and disproportionate and in particular, contravened Mr. Thomas’ constitutional rights and was otherwise contrary to the rule of law.

Justice Rampersad concluded that the sole reason for Mr. Thomas’ detention in Barbados was for him to be deprived of his liberty sufficient for ASP Birch and SS Martin and Corporal Joefield (TT police officers) to go to Barbados and return Mr. Thomas to TT under their custody. They obviously had no jurisdiction to detain the first claimant in Barbados. The intention, therefore, was to have him detained there and to forcibly abduct him under the pretence of police legitimacy since there was no evidence that Mr. Thomas accompanied the police contingent from TT willingly.

In addressing the issue of Barbados’ role Rampersad J. noted that there was no doubt that Barbados was a Commonwealth territory for the purpose of the Extradition (Commonwealth and Foreign Territories) Act Chapter 12:04 of the laws of TT. Barbados had also enacted its own international obligations in relation to extradition in its Extradition Act, 1979. Therefore, the rule of law and due process of law would have been easily attainable by following the process thereunder. However, the process was not followed. Instead, it is undoubtedly an inescapable inference that the Barbados Police Force detained the first claimant upon the request of the Trinidad and Tobago Police Service.

Concerning the abduction Rampersad J. said: “Words cannot express the abhorrence that the court feels towards this unlawful act in a supposed civilized society governed by a Constitution in which the freedoms of the citizens are supposed to be protected.”

Constitutional relief was granted including damages, for the breach of the claimants’ constitutional rights. Thomas v. the AG and DPP Claim No. CV2022-04567

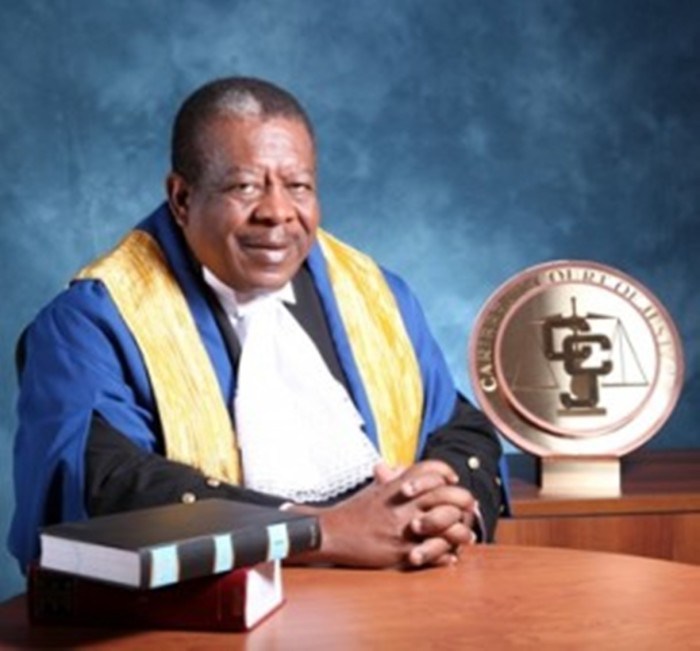

In Shanique Myrie v. The State of Barbados [2013] CCJ 3, the Caribbean Court of Justice (“the Court”) sitting in its original jurisdiction was faced with an issue of major importance, that is, whether and to what extent CARICOM nationals have a right of free movement within the Caribbean Community.

In Shanique Myrie v. The State of Barbados [2013] CCJ 3, the Caribbean Court of Justice (“the Court”) sitting in its original jurisdiction was faced with an issue of major importance, that is, whether and to what extent CARICOM nationals have a right of free movement within the Caribbean Community. The Court was then met with the question, whether article 240 of the RTC requires the 2007 Conference Decision to be enacted at the domestic level before it becomes binding on that particular Member State. Article 240 (1) and (2) states:- 1. Decisions of competent Organs taken under this Treaty shall be subject to the relevant constitutional procedures of the Member States before creating legally binding rights and obligations for nationals of such States. 2. The Member States undertake to act expeditiously to give effect to decisions of competent Organs and Bodies in their municipal law.

The Court was then met with the question, whether article 240 of the RTC requires the 2007 Conference Decision to be enacted at the domestic level before it becomes binding on that particular Member State. Article 240 (1) and (2) states:- 1. Decisions of competent Organs taken under this Treaty shall be subject to the relevant constitutional procedures of the Member States before creating legally binding rights and obligations for nationals of such States. 2. The Member States undertake to act expeditiously to give effect to decisions of competent Organs and Bodies in their municipal law. In the event that a Member State denies entry to a CARICOM national, that State is required to give to the person reasons for the denial of entry promptly and in writing. The Court expressed the view that it would be reasonable to permit persons who have been refused entry the opportunity to contact an attorney or consular official of their country or a family member.

In the event that a Member State denies entry to a CARICOM national, that State is required to give to the person reasons for the denial of entry promptly and in writing. The Court expressed the view that it would be reasonable to permit persons who have been refused entry the opportunity to contact an attorney or consular official of their country or a family member.